How AI Works Part Two: Data, Algorithms, and THE CALL IS COMING FROM INSIDE THE HOUSE!!!

Also, it’s time to eat your broccoli.

One of the things that I have been doing as part of my sabbatical in Fall 2025 is working with a group of educators on using AI for teaching and learning. I’ve found that many of them are, understandably, very interested in finding useful AI tools and learning how to prompt an AI tool more efficiently. I completely understand that and help them do that.

But the more I learn about AI the more convinced I am that people need to have a better understanding of how AI works so that we can make informed decisions about AI use and the impact of AI on our societies. At the moment, all of the decisions about AI in the US are being made by AI companies. And given that the US is a leader in AI, what happens in the US will impact the rest of the world as well.

One of my biggest concerns about AI is that AI tools are released to us and we must react to them. We can’t plan for their use proactively because we don’t know what they will do. Sometimes new releases can be really useful, like Google’s updates to NotebookLM which can produce multimedia from long text files [Link here]. And sometimes it might be less useful, like ChatGPT’s “Mature Mode” [Link here]. Or their new Sora App which makes Deep Fakes easy and generates AI slop at scale [Link here].

If we have no say in what AI can do, will do, or should do, we will not be able to plan for its potential impact. I’d like to help change that. Which means we need to know more than what tools to use. You need to know how AI works. To be fair, it is less fun than cool AI apps.

So I make people eat their broccoli and talk to them about things like training data, algorithms, and AI output integrity. I think that is important, so I’m going to write about it here for you as well. So get ready to eat your broccoli.

An AI generated image of a teacher serving broccoli to some skeptical students.

How AI Gives Us an Answer

AI is great at generating content. But that content is not always useful or accurate. The quality of the content AI produces is known as output integrity. We are told constantly by everyone, including the AI companies, that we should always verify the AI’s output for accuracy. Verifying AI output, whether it is correct or not, is time consuming and challenging to be sure, but if you’re a teacher using AI output in your classes, you have to make sure your students are seeing accurate information. If you are a company using AI, when you release AI output under your brand name you have a business and financial incentive to make sure the information you are releasing is accurate. A better understanding of what algorithms do and how they work can help you better evaluate output integrity.

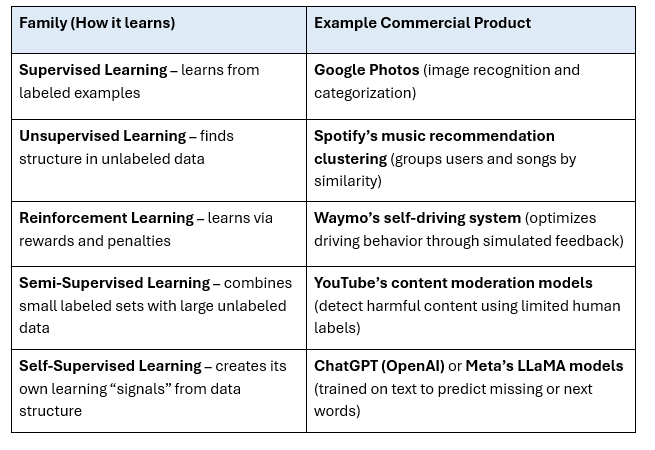

To help simplify discussions of algorithms, I use two categories: Algorithm Families and Algorithm Types. I group algorithms into families (how they learn) and types (what they do). (NOTE: AI professionals use “algorithm families” to refer to model architectures (e.g., decision trees, neural networks, Bayesian models), rather than learning paradigms. “Types” can also overlap with “tasks” or “applications,” depending on context. So consider my framing appropriate for AI curious users a conceptual simplification and not an industry-standard taxonomy.)

But First, Training Data

We all know that AI is trained on data. Lots and lots of data. Most generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, etc. are trained on data that is “scraped” from the Internet, meaning it was gathered using tools that collected the information often without the knowledge or approval of the content’s owner. One of the reasons that a generative AI tool can generate (yes, that’s what it means) reasonably well written text is because it was trained on reasonably well written text. And that text is the data it was trained on. As you know, data is not just text, but it includes pictures, art, video, audio, and any combination of any of these things that might be available digitally.

You may find it interesting to know that facial recognition, one of the most widely used, and controversial, AI applications in use today, was trained on Flickr photos. Do you remember Flickr?

Flickr was one of the earliest image sharing platforms and was very popular from around 2004 - 2013 or so. And AI companies routinely trained facial recognition systems on Flickr photos. While most people sharing their photos realized they were putting their picture in the public domain, they likely did not realize that their pictures were being used by companies like IBM and NVIDIA to develop AI tools. And while the “Terms of Use” may have said something like, “We may share certain data with trusted partners….” Most users likely weren’t aware exactly what that meant or who the trusted partners were. And it is also true that companies using Flickr photos, or Flickr itself, may not have been as transparent about what they were doing as they could have been. Keep that thought in mind.

But! Once you have all of that data, the AI needs to learn the data. That’s an Algorithm Family. Here. Have some more broccoli.

Algorithm Families

Algorithm Families are how the AI “learns” or operates. This is the algorithm an AI system uses to train itself on the massive amounts of data it is fed such as text and images. An algorithm is simply a set of instructions, so think of this algorithm as the instructions the computer uses to manage and learn from all of the data it has. These algorithms are often referred to as paradigms or learning approaches in AI research and practice, and you see them in practice in the commercial products you use.

Once the AI is trained on the data, then it needs to figure out how to give us an answer that we can use. That’s an Algorithm Type. And a little more broccoli.

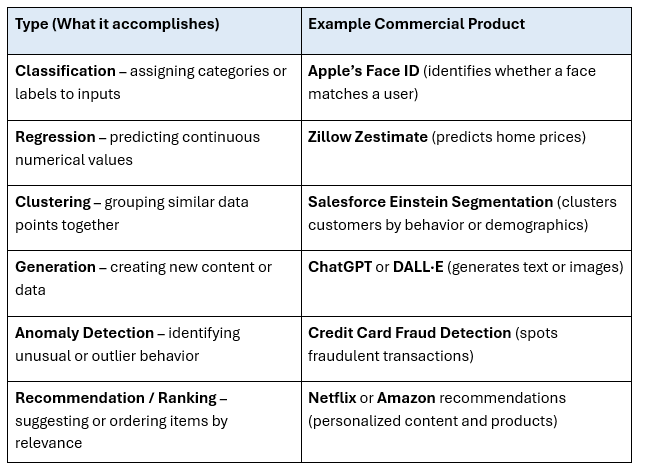

Algorithm Types

An algorithm “type” means what the AI system is designed to accomplish or produce. Or, to use the language from above, how it generates the AI output. So, once the AI is trained by the “Family” the “Type” might be thought of as how it creates the output you see. This output shows up in many AI commercial products we all use.

How the Magic Happens

Modern AI systems often combine multiple learning families in the same overall model or training pipeline. In fact, most state-of-the-art AI today is hybrid in this sense, using multiple learning families to train data. Similarly, an AI system may use multiple types to produce a product. For example, an AI system may need to classify data before making a prediction. It may need to rank results after clustering them. But before any AI system can be used, the algorithm families need to teach it how to use the data and the algorithm types need to be working to give you your final output.

AI may seem like “magic,” but really it is a set of these algorithms working together to give you an outline of a history paper, a recipe for Panang Curry, a picture of a rabbit riding a motorcycle, a rubric for grading student dioramas, or a Sea Shanty about Paul Bunyan.

Is it important for me to memorize different types of algorithms?

Probably not. I don’t. If you’re not an AI professional, the AI algorithms will likely be transparent to you. And normal people don’t really do much with the algorithms beyond using them to generate what we need.

However!

The people who control the training data and the algorithms control the AI. And that is important for you to know. People who control the AI will determine what data the AI is trained on, how the AI is trained, and what the AI system will actually do. In AI safety “algorithm transparency” is critical. Transparency is when the AI companies tell you what families and types they are using and what data they trained on. OpenAI is pretty open about this. I asked ChatGPT what families it was trained on, and it provided way more than you want to read, but it also provided a helpful, I think, summary:

“OpenAI trained me using a multi-family pipeline — self-supervised learning for foundational knowledge, supervised learning for task refinement, and reinforcement learning for alignment with human values and communication style.”

If we don’t know what data an AI is trained on (training data), how the AI is trained (algorithm family), and how it plans to use its data and data training (algorithm type), we can’t reasonably assume that the data output is not somehow biased and as such, not trustworthy or accurate. The same thing is true if we can’t trust the AI company to be honest with us about these things. Am I suggesting AI companies may not be honest with us? No, but I am suggesting that there is a lot of money involved in these AI systems and money can make people do strange things.

Imagine an AI System

So this is what I told my workshop participants about data and algorithms. And then I asked them to imagine an AI system that could do something to make their professional life easier or more efficient. One group of teachers came up with this really great idea:

An AI that could grade student work and provide feedback in a voice that was identical to the teacher’s voice.

Teachers know that one of the most important things they do is to provide good feedback to students to help them get better. People don’t learn more because we tell them when they are right or wrong. People learn more when we help them dig deeper and explain to them how they can get better. Teachers also know how incredibly time consuming providing informative feedback is. Ask any teacher what the hardest part of their job is and they will likely put grading and feedback near the top or at the top of their list. An AI system that could provide good feedback well and in my voice? That would be a game changer!

We talked about what kinds of algorithm families they might use and what algorithm types might be needed to produce an AI system to help with grading. But what was really illuminating was when we talked about the data you would need to train the AI system.

When I asked the group what kind of data would be needed to train an AI that could identify student mistakes and provide feedback in the voice of the teacher, a participant said:

“You might need some samples of our students’ work to see what kinds of mistakes they usually make. And you might need some examples on how I respond to particular mistakes so it could learn to respond like I would.”

And then they stopped speaking and just stared at me.

“Where might they get this data,” I asked. And they looked at me and said with a bit of fear and wonder, “From our Learning Management System.”

And that, my friends, is what we educators might call an “Ah ha!” moment.

Ah Ha!!!

Schools and universities around the world use Learning Management Systems (LMS) for students to access assignments, turn in their work, take exams, and get grades and feedback. You may know the names of LMSs like Blackboard, Google Classroom, Canvas, or BrightSpace Desire 2 Learn. We use LMSs to communicate with our students through private messages and public discussion boards. Teachers upload readings, original teaching materials including text, audio, and video to the LMS in a digital format. And what do we know about AI training data? It can be anything that exists in a digital format. And what is inside of a Learning Management System? A lot of information in a digital format. For a teacher to make the connection that student and teacher data from an LMS might be used for AI training is a little like finding out that the call is coming from inside the house.

Are LMS companies using student and teacher data for AI training? From my research the answer is, maybe? What they are doing is backing up all of our classes on their servers. What they are doing is sharing data with “trusted partners to improve the system.” Does that mean they are using our data to train AI? Again, maybe? They certainly have the opportunity to use it for AI training, or marketing, or anything else. And based on the contracts schools and universities sign, they may even have the right to do this. After all, academic publishers are selling their entire catalogs to AI companies as training data without the knowledge of the people who wrote the papers. You may think that is shady, but is also likely permissible under the agreements scholars sign but maybe don’t quite fully understand [Link here]. Remember Flickr?

My Friend Flickr

From my reading and understanding of what Learning Management Systems do, they certainly are using this data. Oh, they may be anonymizing it, disaggregating it, and maybe even curating it to remove sensitive content, but it is still data that is likely being used without a lot of people’s understanding. And it is still really valuable data. Should we give it away for free? Should we be paying them to take our valuable data? I don’t have a definitive answer to that, but if I were an Associate Vice Provost for online learning, and did not know the answer to those questions, I’d be consulting legal counsel and looking at contracts and what we agreed to sooner rather than later.

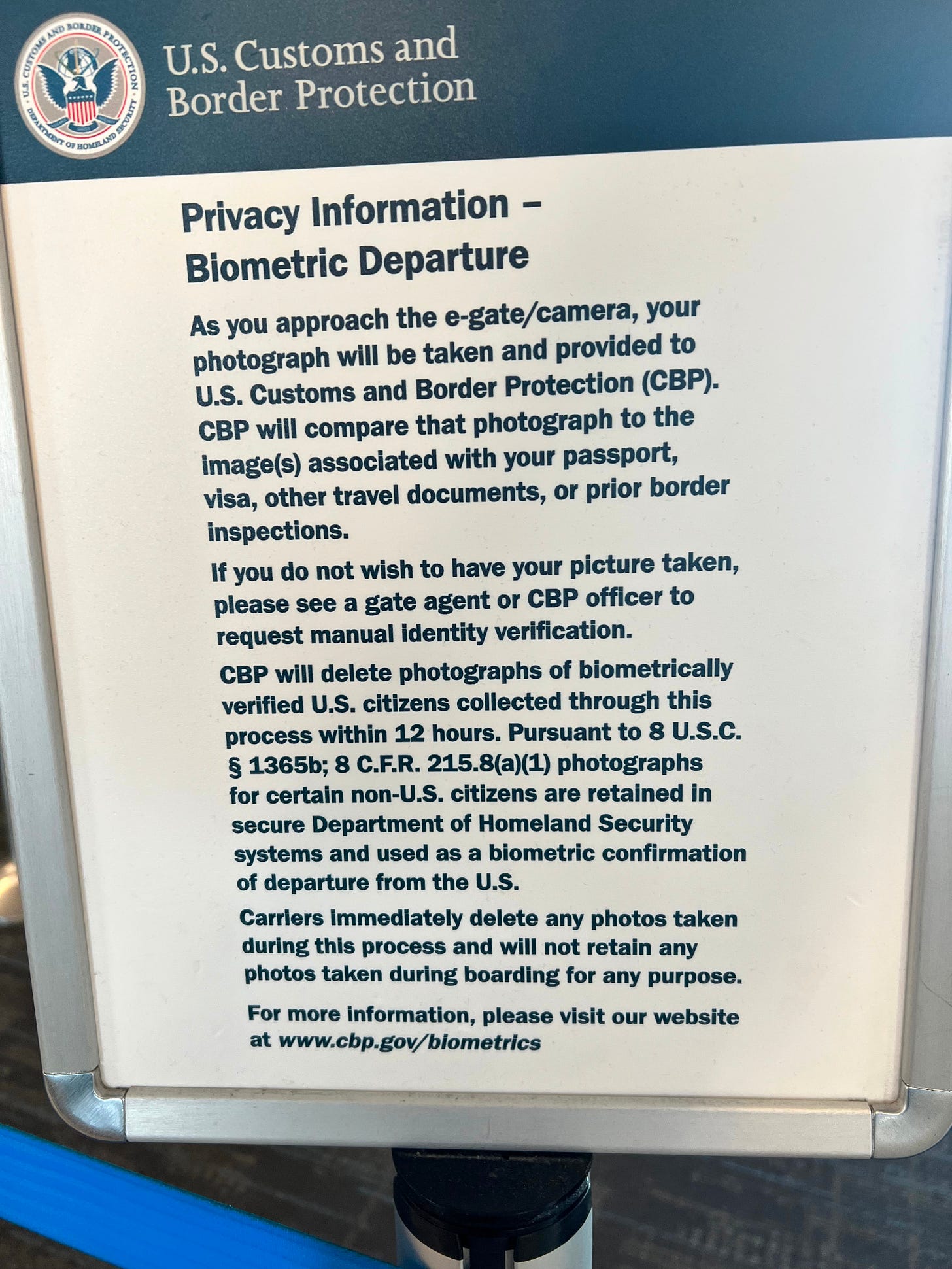

I’m not here to single out Learning Management Systems. To be fair, everything we use is collecting data on us. Our banks, our video streaming services, our grocery store, our online store, and all of the online services we use are collecting our data. When you take a walk in your neighborhood your neighbors’ doorbell cameras are collecting data on you. If you fly in the US, your picture is taken and compared to a variety of sources that also have your picture to verify it is you traveling. I took this photo on a recent trip.

And the list goes on. Is it a good thing or a bad thing to have all of this data collected on us? I think in many cases it isn’t good, particularly when companies or governments don’t tell us they are collecting our data. But I’ll grant that opinions vary and that I do appreciate how fast I can clear customs in the US because they have so much data on me.

Final Thoughts

I’m hoping to make the larger point that we simply don’t know what is being done with our data, much like people in 2007 didn’t know their Flickr photos were being used to create facial recognition AI. And companies who developed those systems made a lot of money training on a set of data for free. I’m not here to accuse LMS companies, online shopping portals, or anybody else of doing something untoward. But I am here to say that every time we agree to “Terms of Service” to any online system like a Zoom meeting, a Slack group, or an online retailer, we are likely agreeing to give away very valuable information about us for free to companies who will use it to make money. Is it worth it? I’d wager that sometimes it is and sometimes it isn’t.

BUT!

Should we at least have a say in how are data is used? Should there be regulations related to data transparency? I think yes and I encourage my elected officials to create laws related to this. You should too. But in the meantime, we all need to practice better due diligence with our digital footprints. And companies need to be more transparent in how they tell us about what they will do with our data. Because if we have any chance of being more proactive and less reactive to AI it will require all of us to pay much more attention. So I hope you like broccoli.

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading. More anon.